Chapter 2 - The deployment of the NZSAS to Afghanistan: political and constitutional dimensions

< Return to Contents | Previous | Next >

The deployment of the NZSAS to Afghanistan: political and constitutional dimensions

Chapter 2

- This chapter deals with various matters that provide important context for issues that we are directed to consider. We begin by providing some brief background on Afghanistan, its history and the impact that various conflicts have had on the population. We then describe the New Zealand deployments to Afghanistan and the basis for them, with particular reference to the initial deployment in 2001 and the deployment of the New Zealand Special Air Service (NZSAS) in 2009.

- This leads on to a discussion of the nature of the NZSAS deployment in 2009 as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), and requires consideration of issues relating to command and control. We outline the constitutional position of the military in New Zealand, focusing particularly on two important issues—civilian control and ministerial accountability to Parliament. This is necessary background to two of the questions raised in our Terms of Reference. The first is “whether there was any ministerial authorisation of the Operations”, which we consider at the end of this chapter.1 The second is whether, if the relevant rules of engagement “authorised the predetermined and offensive use of lethal force against specified individuals (other than in the course of direct battle)”, responsible ministers understood that.2 We address the detail of this second question in chapter 7.

- In his informative book on the history of Afghanistan, Thomas Barfield describes the country as holding a key geographic position linking “three major cultural and geographic regions: the Indian subcontinent to the southeast, central Asia to the north, and the Iranian plateau in the west”.3 As a result, Afghanistan was the target of invaders over many centuries and for much of its history was incorporated, at least in part, into the empires of various foreign leaders. Equally, at various times Afghan leaders led incursions into India and other neighbouring countries, as William Dalrymple graphically describes in his book, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company.4

- More recently, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the British fought three wars in Afghanistan which were largely driven by a perceived need to counter Russian expansion. None ended particularly well for the British. More recently again, troops from the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, at a time when the communist government then in power in Afghanistan was involved in a conflict with anti-communist mujahideen. The Soviet troops met with strong local resistance (supported by a number of countries, including the United States) and ultimately withdrew ten years later, again without significant success. It is for good reason that Afghanistan is referred to as “the graveyard of empires”.5

- Reflecting Afghanistan’s geographical position and turbulent history, its population comprises a complex mix of different ethnicities, different languages and different religious beliefs/practices. Barfield describes the outstanding social feature of life there as being its local tribal or ethnic divisions. He writes “[p]eople’s primary loyalty is, respectively, to their own kin, village, tribe, or ethnic group, generally glossed as qawm.”6 There is no significant adherence to a central government.

- Many parts of Afghanistan are marked by extreme poverty and subsistence living. The country has a high illiteracy rate.7 We heard evidence that malnutrition is common and Afghanistan remains one of the most dangerous places in the world to be an infant, a child or a mother.8 Among the population, there are high levels of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, resulting from the long-running conflicts and other circumstances of daily life.9 Corruption and criminal activity (much of it drug-related) are endemic.10

- One result of the interminable wars in Afghanistan, particularly the conflict with the Soviet Union in the 1980s, is that military-style weapons are widespread. Rivalry and feuds are commonplace, although allegiances do change as circumstances change. Warlords and private militias have played a significant part in Afghanistan’s history, even in recent times. Between 1992 and 1996 Afghanistan endured civil war, during which warlike militias effectively ruled the country, leading to the emergence of the Taliban.11 In her book Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan to a More Dangerous World, war correspondent Christina Lamb describes the many difficulties faced by President Hamid Karzai in the early/mid-2000s, commenting that “… in a country where anyone that mattered had their own militia, he had no one”.12 In such a setting, locals may see weapons such as AK-47s as necessary to protect themselves and their families, particularly in remote or rural areas.13

- New Zealand’s involvement in Afghanistan began in 2001 “as part of international counter-terrorism operations directed against Osama bin Laden, al-Qaida, and the Taliban following the 9/11 attacks in the United States of America.”14 Before we outline the process leading up to the Government’s decision to deploy troops to Afghanistan, we provide a brief overview of the international community’s response to 9/11. This response was within the framework of the Charter of the United Nations (the UN Charter), the starting point of which is that states should settle their international disputes by peaceful means but which then recognises certain exceptions.15

- On 12 September 2001, the day following the 9/11 attacks, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1368. This resolution recognised the right of individual or collective self-defence and condemned the attacks as acts of international terrorism which were a threat to international peace and security. The resolution called on the international community to bring those responsible to justice and to work together to prevent further attacks.16

- Resolution 1368 was passed against the background that a Taliban Government held power in Afghanistan and permitted al-Qaida leadership to live and operate training camps there. As Cornelius Friesendorf observed: “… al Qaeda, under the leadership of Osama bin Laden, supported the Taliban financially to the point that the Taliban became dependent on al Qaeda and Bin Laden’s personal wealth.”17

- In the months that followed, the Security Council passed further relevant resolutions:

- On 28 September 2001 the Security Council passed Resolution 1373. Acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the Security Council decided that states should take a number of measures to prevent the financing and commission of terrorist acts.

- On 12 November 2001 the Security Council passed Resolution 1377, which adopted a declaration on the global effort to combat terrorism. It declared that acts of international terrorism constituted a serious threat to international peace and security in the 21st century and that “a sustained, comprehensive approach involving the active participation and collaboration of the Member States of the United Nations, and in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and international law, is essential to combat the scourge of international terrorism”. It called on all states to implement Resolution 1373.

- On 14 November 2001 the Security Council passed Resolution 1378. Among other things, the resolution expressed its “strong support for the efforts of the Afghan people to establish a new and transitional administration leading to the formation of a government …” It affirmed that the United Nations should play a “central role” in supporting those efforts.

- On 6 December 2001 the Security Council passed Resolution 1383, which endorsed provisional arrangements in Afghanistan until permanent government institutions were re-established. These arrangements were set out in the Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Re-Establishment of Permanent Government Institutions (the Bonn Agreement).18 The arrangements established the Afghan Interim Authority to govern the country for six months while a Transitional Authority was appointed.19

- On 20 December 2001 the Security Council passed Resolution 1386. Acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, the Security Council authorised the establishment of ISAF for six months at the request of, and to support, the Afghan Interim Authority. ISAF’s role would be to “assist the Afghan Interim Authority in the maintenance of security in Kabul and its surrounding areas”. The resolution called on Member States of the United Nations to contribute to ISAF with personnel, equipment and other resources. Member States participating in ISAF were authorised to “take all necessary measures to fulfil its mandate”. (Resolutions in subsequent years enlarged the territorial scope, and extended the length, of ISAF’s mandate. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) assumed the leadership of ISAF in 2003.20)

- On 28 March 2002 the Security Council passed Resolution 1401. It established the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA).21 The resolution stressed recovery and reconstruction assistance to help implement the Bonn Agreement. It urged donors to respond.

- We should also note that from late 2002, the United States began to establish Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) in Afghanistan.22 These were combined military/civil units which were intended to facilitate reconstruction of infrastructure and suchlike in Afghanistan, to enhance security and to reinforce and extend the authority of the Afghan Government. Over time, individual countries took responsibility for particular PRTs. Much of the PRT funding came though ISAF programmes.

- One important restriction on the use of force in international relations flows from art 2 of the UN Charter. Article 2(3) obliges States to settle their disputes by peaceful means, and art 2(4) limits the use of force or the threat of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. These restrictions are, however, subject to the inherent right of self-defence in art 51, which provided the basis for the initial involvement of the United States (and New Zealand) in Afghanistan in Operation Enduring Freedom, a United States-led coalition. They are also subject to the authorisation of the use of force under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, which the Security Council invoked when establishing ISAF. As noted, Resolution 1386 authorised participating member states “to take all necessary measures to fulfil [ISAF’s] mandate.”

- The Inquiry sought an expert opinion on the applicable law from Emeritus Professor Sir Kenneth Keith QC, a former Judge of the International Court of Justice. He told the Inquiry that Resolution 1386 authorised the use of armed force, and that was how the resolution had been understood in practice.23 The Inquiry accepts this and notes that the resolution did not limit ISAF to using force defensively. Thus, ISAF often undertook planned offensive action targeting insurgent groups to fulfil its mandate of maintaining security. The Inquiry agrees with Professor Keith that any use of force by ISAF had to be consistent with international law. The Inquiry also agrees with Professor Keith’s view, again reflecting the international consensus, that the language from the Security Council resolution provides authority for the detention of persons in Afghanistan.24

- As can be seen from the foregoing description, the international community reacted strongly to the 9/11 attacks, calling on member states to take a range of military, reconstructive and humanitarian steps. The United States-led Operation Enduring Freedom, the NATO-led ISAF coalition, UNAMA and the PRTs operated for much of the period of New Zealand’s involvement in Afghanistan, reflecting a multi-faceted approach. Operation Enduring Freedom and ISAF were separate, but to some extent overlapping, in their military operations and ran alongside each other.

- The deployment of New Zealand forces to Afghanistan began in 2001 with a deployment of the NZSAS for 12 months, in 2004 for six months, in 2005 for six months and from 2009 until 2012.25 New Zealand assumed responsibility for the PRT in Bamyan province in 2003 and was active there until 2013. We now describe the background to the initial deployments of the NZSAS in 2001 and the New Zealand Provincial Reconstruction Team (NZPRT) in 2003 and then describe the deployment of the NZSAS in 2009.

The initial NZSAS deployment in 2001

- New Zealand responded to the call of the United Nations in 2001 for assistance in Afghanistan, as did many other nations. Then Prime Minister Rt Hon Helen Clark announced in a media release on 21 September that New Zealand would make a military contribution. (The first deployment of NZSAS arrived in Kandahar in December 2001). A parliamentary debate about this decision was triggered on 3 October 2001, when the Prime Minister moved the following resolution:26

That this House declares its support for the offer of New Zealand Special Air Service troops and other assistance as part of the response of the United States and international coalition to the terrorist attacks that were carried out on 11 September 2001 in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania.

- A lengthy debate followed, in which all political parties represented in the House of Representatives took part. The debate took place shortly before the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.27 Various amendments were moved. The resolution that finally passed included the following additional words (added by amendment):28

… and totally supports the approach taken by the United States of America, and further declares its support for United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1368 and 1373.

- The Prime Minister pointed out to the House that the offer to deploy what she characterised as “New Zealand’s crack troops” was made because New Zealand people were not neutral about terrorism and they wanted their country to be part of the effort to combat it.

- The parliamentary resolution in its amended form passed in the House by 112 votes to 7, with only the Green Party voting against it. As in other nations, there was wide cross-party support for sending New Zealand troops to Afghanistan in response to the Security Council’s call for assistance from the international community. The New Zealand commitment initially was to Operation Enduring Freedom, but later it was to ISAF. In addition to forming part of the ISAF presence in Afghanistan, which was mandated by the Security Council resolutions referred to above, the deployment of New Zealand troops was also supported by direct arrangements between New Zealand and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (Afghan Government).29 This enabled New Zealand troops to conduct national tasks as well as ISAF operations, as we discuss further below.30 By the time ISAF transitioned to Resolute Support Mission in 2014, 51 nations had contributed to the international effort by providing military or police assistance in Afghanistan.31 Nineteen nations were there by January 2002.

- The fact that the NZSAS was deployed initially was facilitated by the contact its leaders had already had with United States Special Forces a few weeks before 9/11. On a visit to Tampa, Florida and to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, described in Ron Crosby’s book on the NZSAS, Lieutenant Colonel Tim Keating (then Commanding Officer of the NZSAS) and his successor designate, Lieutenant Colonel Jon Knight, established a good working relationship with United States Special Forces. This relationship had developed during New Zealand’s involvement in Kuwait in 1998 as part of a joint contribution with Australia.32

- A squadron of NZSAS soldiers landed in Afghanistan on 9 December 2001, shortly after the collapse of the Taliban Government as a result of United States-led attacks. By then al-Qaida leaders, including Osama bin Laden, had escaped from the mountain fortress of Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan into Pakistan. It is important to recall that the Taliban, who at the time were largely Pashtun and tended to view other ethnic groups as enemies, had never created a real government in Afghanistan despite controlling much of the country.33 As a result, after the collapse of the Taliban regime, there was little left upon which to build. As Thomas Barfield noted:34

… the United States invaded Afghanistan at a time when the state structure had ceased to function. It would need to create a new state to restore stability to the country.

- The Taliban regime had caused or led to significant negative outcomes for Afghanistan and its people. For example:35

- Its enforcement of Sharia law had included inflicting harsh punishments.

- Women had few rights and freedoms.

- Many institutions and much of the country’s infrastructure were badly damaged or destroyed.

- Much productive land had become unproductive.

- Particular ethnic groups had been preyed upon (for example, the Hazara people).

- Cultural genocide had occurred, most notably the destruction in 2001 of 6th century Buddhas in Bamyan province.

- Thousands of homes were destroyed.

- Millions of people had fled to neighbouring countries, particularly Iran and Pakistan, to live as refugees. After the United States invaded, several million of them returned to Afghanistan, creating further difficulties.

- The international community considered that it was necessary to re-build the capacity of the Afghan people to conduct their own government and their own defence and to support the reconstruction and development of the country.36 One result was the increased focus on PRTs, which led to New Zealand troops being deployed in Bamyan province as the NZPRT from 2003 until April 2013. As Sir Angus Houston, the former Australian Chief of Defence Force, told the Inquiry, “[t]he PRTs were central to ISAF efforts across Afghanistan and were the heart of the counter-insurgency effort, or more widely known as COIN.”37

- On 8 July 2003 the New Zealand Minister of Defence, Hon Mark Burton, announced the new NZPRT commitment.38 The Minister said the NZPRT had a focus “on enhancing the security environment and promoting reconstruction efforts.” The NZPRT was more of a security and reconstruction force than a combat unit, albeit that it undertook security patrols which, on occasion, did lead to combat. The NZPRT consisted both of military personnel and civilians. In 2012 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) became the lead agency for the NZPRT, taking over from the New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF).39 From that time until the NZPRT ceased operations in 2013, NZDF’s senior officer in the NZPRT deployment took the title of “Senior Military Adviser to the PRT” as well as Commanding Officer of CRIB (the NZDF operation name for the NZPRT deployments).40

- Between 2004 and 2011 “NZDF was involved in more than 200 projects, large and small, that assisted the people of Bamyan.”41 The NZPRT’s official purpose was to establish a stable and secure environment in which local people could rebuild their province with the support of the Afghan Government, New Zealand and other donors. The New Zealand contribution included police resources, development assistance, education, governance, justice and the rule of law, health, humanitarian assistance and reconstruction elements.42

- The Security Council passed numerous resolutions in relation to Afghanistan from 2002 to 2009, the detail of which we do not need to address. However, two points relevant to the issues before the Inquiry are worth noting:

- First, the Security Council stated on a number of occasions that Afghan authorities were responsible for providing security and law and order throughout Afghanistan.43 ISAF and other partners were encouraged to continue their efforts “to train, mentor and empower the Afghan national security forces, in particular the Afghan National Police”.44

- Second, a number of resolutions relating to Afghanistan incorporated the Security Council’s general resolutions calling for the protection of civilians in armed conflicts.45

- In addition to the ongoing NZPRT deployment, in 2009 the NZSAS was deployed to Afghanistan for the fourth time, as part of ISAF. This was consistent with other nations’ involvement and reflected the focus of the international community on state-building in Afghanistan. As we noted earlier, Operation Enduring Freedom was a United States-led coalition combat operation, part of the United States’ global war on terror, while ISAF was a NATO-led coalition operation, concentrating on security assistance and helping Afghan authorities rebuild key government institutions. Both operations ran concurrently in Afghanistan for more than a decade. United States forces could be assigned to one or both operations and the Commander ISAF was also the Commander of United States Forces in Afghanistan (USFOR-A).

- The international community recognised that progress was needed on security if proper governance arrangements were to be established. Development assistance could not succeed without effective security, proper governance, application of the rule of law and the absence of corruption. Achieving these was essential for a proper functioning state, but proved a major challenge.

- The decision to deploy the NZSAS in 2009 was made by the National-led Government of Rt Hon (now Sir) John Key.46 In February 2009, the Cabinet had decided to extend New Zealand’s existing commitments in Afghanistan (principally the NZPRT) from 1 October 2009 through to 30 September 2010. Cabinet also agreed that there should be a review of New Zealand’s commitment in Afghanistan beyond 30 September 2010, with the results to be provided by mid-2009.

- In March 2009 the Government received a request from the United States for a further deployment of the NZSAS to Afghanistan, beginning in September 2009. This was one of several requests made by ISAF and United States authorities, the most notable of which was in a telephone call from United States President Barack Obama to Mr Key47. The proposal was that the NZSAS would, at least temporarily, replace the withdrawing Norwegian Task Group. Like the Norwegians, the NZSAS would partner with the Afghan Crisis Response Unit (CRU) in a mentoring role.48 In his evidence, Hon Dr Wayne Mapp, who was the Minister of Defence at the time, said that the United States military hierarchy regarded the NZSAS highly as a Tier 1 Special Forces group—well trained, professional and capable of handling difficult missions successfully.

- In July 2009 the Cabinet established a group of ministers with Power to Act in relation to the proposed NZSAS deployment, subject to the full Cabinet endorsing its decisions. The group comprised the Prime Minister, the Minister of Finance (Hon Bill English), the Minister of Foreign Affairs (Hon Murray McCully) and the Minister of Defence (Dr Mapp). On 10 August 2009 the Cabinet endorsed the group’s decision that the NZSAS would deploy to Afghanistan from late September 2009 for a period of 18 months.49 The tasks which the NZSAS was to perform were:50

- conducting reconnaissance in Kabul and adjacent provinces to locate insurgent forces and improvised explosive device networks;

- both training and mentoring the CRU;

- direct action against insurgent networks in support of ISAF and the Afghan Government; and

- national tasks, including (most relevantly) supporting NZDF elements in Afghanistan.

- A number of features of the Cabinet’s decision are pertinent given the issues before the Inquiry. In particular, the Cabinet noted that:51

- the deployment was authorised by various Security Council Resolutions;

- there were national caveats for the deployment;

- the Prime Minister had approved the rules of engagement for the deployment;

- Afghan authorities (such as the CRU) would generally be responsible for detaining individuals, rather than NZSAS, but where the NZSAS detained people, there were procedures in place to deal with that;

- MFAT was continuing to seek formal written assurances from the Afghan Government that detainees would not be subjected to torture or capital punishment;

- the Chief of Defence Force “would retain full command of all NZDF personnel posted or attached as part of the deployment, and that the NZSAS would only accept tasks that they [were] willing to undertake and would be able to decline other tasks” (sometimes described as a national “red card”).

- The decision to re-deploy the NZSAS to Afghanistan was debated in Parliament. An urgent debate on 15 August 2009 was moved by the Green Party, which opposed the deployment. The debate showed that political opinions about the desirability of such a deployment had shifted, compared to those expressed in the debate on the 2001 NZSAS deployment.

- One of the Government’s support parties,52 the Māori Party, expressed firm opposition to the deployment on the grounds that “Afghanistan is not our war, and the SAS should not be going”.53 The Labour Party (by then in opposition) said it was opposed. While in government, it had considered a decision to recommit the NZSAS to Afghanistan, but had decided against it. Hon Phil Goff explained that following the return of the NZSAS in 2005, the Government reassessed the situation and thought the nature of the conflict had changed, becoming a more local conflict between disparate groups. The Progressive Party of Hon Jim Anderton was also opposed.

- Government speakers outlined why the Government had made the decision to deploy. The Minister of Foreign Affairs spoke of the NZPRT’s work and the decision of New Zealand to increase aid “with a greater emphasis on agriculture and continuing high priority … to education and health services”.54 In lifting the level of military support, New Zealand was aligned to the international community.

- The Minister of Defence told the House:55

The challenge is to produce a sufficiently stable Afghanistan so that it does not once again become a haven for terrorists.

Dr Mapp said he had argued for a more sophisticated approach at a NATO meeting earlier in 2009 and a new strategy had been adopted:

It involves an increased commitment of defence forces to build renewed security within the country. The reason for that is to prevent the country from reverting to Taliban control and providing a safe haven for terrorists, particularly al-Qaeda.

- At the Inquiry’s Public Hearing on Module 1 on 4 April 2019, Dr Mapp set out in detail the preliminary work relating to the deployment, the Cabinet processes and the factors that influenced the Government’s decision to deploy as announced on 16 August 2009. These were:56

- a focus on the need to minimise casualties;

- the context of a bipartisan commitment to collective security and a rules-based international order;

- requests from President Obama and ISAF;

- the re-deployment of the NZSAS together with the continuation of the NZPRT deployment advanced the twin aims of ensuring security and facilitating civil reconstruction;

- the need to stop Afghanistan being a haven for international terrorism; and

- the strong support of the Security Council for the remedial steps in governance in Afghanistan and the widespread international support.

- In the result, the Government had majority support in Parliament and the decision to deploy was one it was entitled to make. The NZSAS was accordingly deployed to Afghanistan under the title “Operation Wātea”.

- We begin by briefly describing the context within which ISAF was operating in 2009 when Operation Wātea began and the NZSAS took over the responsibility for training and mentoring the CRU from the Norwegian forces. We then discuss briefly command and control arrangements.

The context

- In his book The Taliban at War 2001—2018, Antonio Giustozzi writes:57

The Taliban Emirate, established in 1996, was in 2001 overthrown relatively easily by a coalition of US forces and various Afghan anti-Taliban groups. Few at the end of 2001 expected to hear again from the Taliban, except in the annals of history. Even as signs emerged in 2003 of a Taliban comeback, in the shape of an insurgency against the post-2001 Afghan government and its international sponsors, many did not take it seriously. It was hard to imagine that the Taliban would be able to mount a resilient challenge to a large-scale commitment of forces by the US and its allies.

- One of the reasons for the rapid collapse of the Taliban Government was the overwhelming firepower that the United States and its allies brought to bear against the Taliban. As Giustozzi graphically records:58

The fall of the Taliban was swift and brutal. Following 11 September 2001, Taliban forces were obliterated in a lightning war prosecuted by American special forces and their Afghan allies, supported by an armada of warplanes. Mullah Cable, a Taliban commander renowned for his toughness, recalls what it was like to be under US bombardment early in the war: ‘My teeth shook, my bones shook, everything inside me shook’. After witnessing his comrades being decimated by the bombing, Cable gathered the rest of his men and told them to go home, before himself deserting.

- However, the Taliban did re-emerge and began to gather strength in terms of both fighters and funding, aided by a perception that the Afghan Government was corrupt and ineffective. Giustozzi considers that after 2005, “the insurgency accelerated considerably”.59 While, historically, the Taliban had been largely of Pashtun origin, this began to change. Over the next several years, the Taliban expanded their influence in various parts of the country, including in non-Pashtun areas such as Tala wa Barfak, the district in Baghlan province where Operation Burnham occurred.60 They melded into the community and were difficult for outsiders to detect. This resulted in asymmetrical or unconventional warfare, which posed a real challenge for conventional armed forces, and led to the adoption of the counter-insurgency strategy (COIN).61 This aimed to achieve three objectives for Afghanistan: governance, development and security. While it involved committing more forces to Afghanistan, COIN was ultimately about winning the support of the Afghan people for the Afghan Government, thereby marginalising insurgent forces. It highlighted the centrality of the treatment of the civilian population to achieving success in Afghanistan.

- The continued reliance by United States and coalition forces on air power in the years after the fall of the Taliban Government came at a significant cost—an increasing number of deaths of innocent civilians. While insurgents caused most civilian deaths in Afghanistan, significant civilian casualties resulted from the actions of coalition forces, including in the course of night operations by Special Forces.62 Such deaths raised issues of accountability, often unanswered.63 As Sir Angus Houston said to the Inquiry:64

The single greatest setback to operational success in Afghanistan was civilian casualties. By far and away it is the innocent civilian population that has suffered the most in Afghanistan. … Potentially for every civilian killed by coalition forces, the saying went you created five to ten more insurgents.

- The leadership of ISAF and USFOR-A understood this and began to address it.65 From 2007, ISAF issued a number of tactical directives and revisions of them (the latter known as fragmentary orders or FRAGOs) to place limits on the use of weapons, particularly air-delivered weapons, so as to minimise civilian casualties. In August 2008, the ISAF Commander, General David McKiernan, established a Civilian Casualty Tracking Cell to gather information on and monitor civilian casualties from coalition activities.66 The following month, he issued a Tactical Directive that limited the use of air strikes in particular circumstances.67 His successor, General Stanley McChrystal, issued a Tactical Directive on 6 July 2009 which was intended (among other things) to limit civilian casualties, particularly from close air support against residential compounds and similar places.68 The directive did not purport to prescribe the appropriate use of force or to prevent commanders from using force in self-defence to protect the lives of their forces where no other options were available to counter the threat effectively.69

- General McChrystal’s successor was General David Petraeus. At his Senate confirmation hearing in June 2010 following his nomination as ISAF Commander, General Petraeus had indicated that a tactical directive was “designed to guide the employment, in particular, of large casualty-producing devices: bombs, close air support attack helicopters, and so forth”.70 He reviewed and amended General McChrystal’s 6 July directive, issuing a replacement Tactical Directive in August 2010, which was in force at the time of Operation Burnham.71 It was considered that the directives were effective in reducing the number of civilian casualties from coalition operations.72

Command and control arrangements

- When deploying personnel to participate in a coalition force, New Zealand does not sign away sovereign responsibility for its forces or allow them to be used without oversight. Consequently, when the NZSAS deployed to Afghanistan in 2009 as part of the ISAF coalition force, several questions arose:

- first was the question of the NZSAS’s role and what, if any, constraints or caveats should be placed on NZSAS operations to ensure the NZSAS was used in a way that was consistent with the Government’s expectations and intent and with the applicable legal obligations;

- second was the question of the applicable command and control arrangements; and

- third was the question of what the NZSAS could do when conducting operations as part of the deployment, which included the question of what controls should be placed on the use of force.

The third of these questions raises the topic of the rules of engagement for the deployment. We address that issue in chapter 6. Here, we make some brief comments on constraints and issues relating to command and control. Before we do so, however, we note an observation made by Sir Angus Houston in his presentation at Public Hearing Module 1, namely that negotiating the labyrinth of command and control, national policy constraints, differing military capabilities and rules of engagement is at the heart of modern coalition operations.73

- Besides the obvious constraints associated with fixing the number of NZDF personnel to be deployed, the length of the deployment and the funds available for it, the Government imposed other constraints (or national caveats) on the deployment. These national caveats were formally communicated to NATO, ISAF and the United States through the Chief of Defence Force and were accepted by all as conditions of the provision of military forces by New Zealand. They were also included as part of the Chief of Defence Force’s orders to the NZSAS.

- We emphasise two of these constraints:

- In terms of ultimate control, the NZSAS remained under the full command of the Chief of Defence Force and was bound by the New Zealand Government-approved rules of engagement, which were intended to reflect New Zealand views and values on the use of lethal force.

- As to the geographic scope of the deployment, the Government decided that the deployment would be focused on Kabul and its immediate surrounding areas, but that the NZSAS would be permitted to conduct operations outside that geographic zone if requested by the commander of ISAF Special Operations Forces. Effectively, this gave the Chief of Defence Force the power to approve operations outside Kabul and its surrounding provinces if he thought it appropriate to do so. Operation Burnham was one such operation.

- The various constraints reflected government policy and were, in effect, a lawful direction from the Government to and through the military chain of command. As noted by Sir Angus Houston, the placing of national constraints and caveats by individual nations on their forces operating in a coalition environment is common. The type of conditions imposed by the New Zealand Government and NZDF on NZSAS operations were similar to those imposed by other nations involved in ISAF.

- The two constraints identified at paragraph [49] lead into the question of command and control. Along with other issues, command and control are addressed in documents published from time to time by NZDF dealing with military doctrine.74 Military doctrine “provides a military organisation with a common philosophy, a common language, a common purpose, and a unity of effort”.75 It is not a topic that we need to discuss in detail in this report. Rather, there are two relevant points to be made.

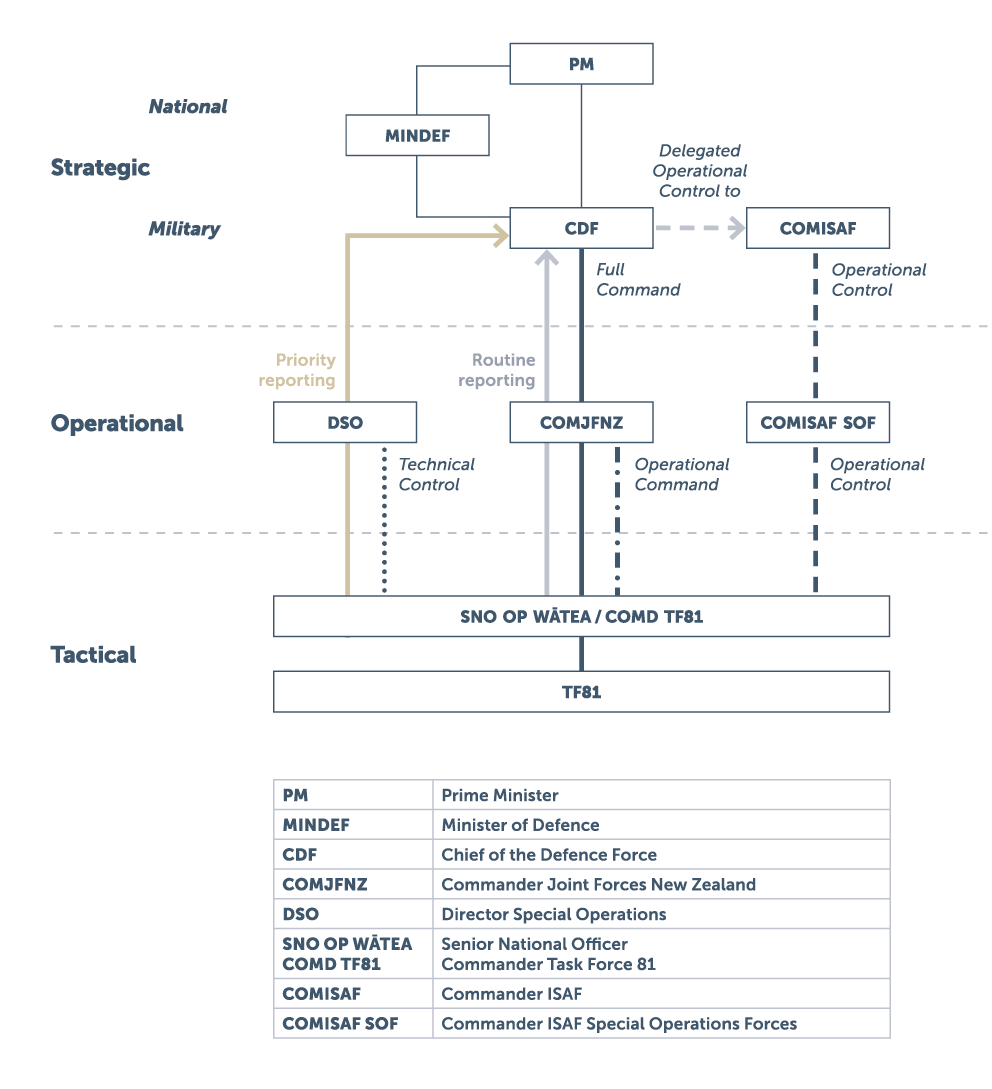

- First, military doctrine identifies decision-making in relation to conflict as occurring at three interrelated levels—strategic, operational and tactical (see Figure 1 at the end of this chapter):76

- The strategic level includes the national political dimension to a conflict and a military dimension. At the national political strategic level, the question is: what strategic objective does the Government seek to achieve by military involvement? The military dimension relates to the way the military supports the national strategic objective—what is the military trying to achieve? How will it go about achieving what it needs to achieve in support of the Government’s objective?

- The operational level deals with the command and planning of military campaigns and major operations.

- The tactical level deals with engagements conducted while executing a particular campaign or major operation. It concerns the practical utilisation of all necessary forces—whether air, land and sea—for the particular conflict.

- Second, military doctrine draws a distinction between command and control.77 In brief, command is the authority which commanders exercise over those who are subordinate to them by virtue of their rank or assignment. Control (in the present context) is the authority exercised by commanders over groups or organisations that are not normally under their command. Operational control is the authority delegated to a commander to direct assigned forces to undertake specific missions or operations.

- Dealing first with command, under the Defence Act 1990, the Chief of Defence Force commands each of the three services— New Zealand Army, Royal New Zealand Navy and Royal New Zealand Air Force—through the chief of each service and commands any joint force through the joint force commander or through the chief of any service.78

- As Cabinet confirmed in its deployment decision, the Chief of Defence Force retained full command of the NZSAS contingent while it was deployed to Afghanistan as part of ISAF. The New Zealand force deployed to Afghanistan comprised an element from NZSAS and some non-NZSAS personnel and was named Task Force 81 (TF81)—it was a separate organisation to the NZSAS based in New Zealand and had a separate commander. In accordance with standing practice, the Chief of Defence Force re-assigned specific elements of his full command to other authorised commanders. The Chief of Defence Force delegated operational control of TF81 in Afghanistan to the Commander ISAF in Kabul and he assigned operational command of TF81 in Afghanistan to the Commander Joint Forces New Zealand, based in Wellington. Commander Joint Forces New Zealand in turn appointed the Commander TF81 as the Senior National Officer, assigning him national command responsibilities in addition to his operational command responsibilities. TF81 had various sub-elements in its structure which Commander TF81 used to achieve assigned tasks.

- Turning to control, operational control of the NZSAS in Afghanistan rested with the Commander ISAF and, through him, with the Commander ISAF Special Operations Forces.79 Operational control involves not simply the ability to direct or authorise missions or operations—it also involves control of processes and requirements for missions or operations. Numerous directives and standard operating procedures were issued by the Commander ISAF over time, some of which are described in more detail in chapter 3.

- In the context of the NZSAS deployment to Afghanistan, the Senior National Officer / Commander TF81 and the Squadron Commander TF81 were required to operate:

- within the constraints imposed by Cabinet and the Chief of Defence Force;

- in accordance with the command and control arrangements made by the Chief of Defence Force; and

- under the relevant rules of engagement.

It must also be emphasised that the Chief of Defence Force held what Sir Angus Houston described as a “national red card”,80 namely the authority to veto the involvement of the NZSAS in a proposed ISAF operation for policy or other reasons.

- To assist understanding, at the end of this chapter is an organisational chart that sets out the command and control structure for the NZSAS’s participation in ISAF (Figure 2).

- A government has available to it a variety of means for pursuing its international objectives, one of which is its military capability. Whether or not it deploys that capability in any given circumstance will often be a matter of intense debate within the government and the country. Obviously, where a country is attacked, the decision is likely to be straightforward—the defence of the nation is one of the fundamental duties of the state. But overseas deployments are likely to be more contentious, as experience of the Vietnam War amply demonstrates.

- In New Zealand, military power is exercised through a combination of statute law and the royal prerogative. The principal statute is the Defence Act. The Long Title sets out the Act’s purposes, three of which are of particular significance here, namely:

- to continue to authorise the raising and maintaining of armed forces for certain purposes;

- to reaffirm that the armed forces are under ministerial authority; and

- to define the respective roles and relationships of the Minister of Defence, the Secretary of Defence and the Chief of Defence Force.

- Section 5 provides that the Governor-General may, in the name of the Sovereign, raise and maintain armed forces whether in New Zealand or elsewhere for certain purposes. Two constitutional scholars, Alison Quentin-Baxter and Janet McLean QC, have stated that s 5 appears to cover every contingency “in which the armed forces might need to be deployed”.81 Most relevant among the authorised purposes in relation to the Afghanistan deployments is the following in s 5(d):

the contribution of forces to, or for any of the purposes of, the United Nations, or in association with other organisations or States and in accordance with the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

Section 6 goes on to provide that by virtue of being the Commander-in-Chief of New Zealand, the Governor-General “shall have such powers and may exercise and discharge such duties and obligations relating to any armed forces raised and maintained under s 5 as pertain to the office of Commander-in-Chief”.82

- However, s 7 makes it plain that ministerial responsibility for the armed forces lies with the Minister of Defence:

Power of Minister of Defence

For the purposes of the general responsibility of the Minister in relation to the defence of New Zealand, the Minister shall have the power of control of the New Zealand Defence Force, which shall be exercised through the Chief of Defence Force.

Various provisions identify the Minister’s responsibility for particular matters. For example, s 13(2) provides that the Minister must authorise the maximum number of officers, ratings, soldiers and airmen in the regular forces; s 15(2) contains a similar requirement in respect of members of the territorial forces. The Minister will, of course, be answerable to Parliament for the exercise of their responsibilities in relation to the armed forces.

- The result is that the power to deploy New Zealand forces abroad “is an element of the executive authority of New Zealand, which is exercisable, through the Governor-General, by Ministers of the Crown, usually acting collectively within Cabinet, but responsible to Parliament for the decisions they make”.83

- Section 8 of the Act provides for the position of Chief of Defence Force. That person is in command of NZDF working through the chiefs of the three armed services—Army, Navy and Air Force. The Chief of Defence Force also commands any joint force established under s 12 of the Act through the Commander Joint Forces New Zealand (or, if applicable, through one of the service chiefs)84 and exercises control over NZDF’s civilian staff.85 One of the most important of the prerogative powers relating to armed conflict and other operations is the power of command.86

- Under s 25(1)(a) of the Act, the Chief of Defence Force is the principal military adviser to the Minister, the Secretary of Defence being the principal civilian adviser.87 Importantly, s 25(1)(b)(i) provides that the Chief of Defence Force is responsible to the Minister for carrying out the functions and duties of NZDF including those imposed by the Government’s policies. Further, under s 25(2) of the Defence Act the Minister is under a statutory duty to provide the Chief of Defence Force with Terms of Reference that deal with matters such as the obligations and duties of the office and how the Chief of Defence Force is to perform them.

- In his 2002 review of the accountabilities and structural arrangements between the Ministry of Defence and NZDF, Mr Don Hunn, a former State Services Commissioner, made the following pertinent observations:88

2.7 As far as the Constitution is concerned there is no room for doubt that both the military and civilian members of the defence system are responsible and accountable to the Government of the day through the Minister of Defence. While the differences between the two are recognized in a number of ways there is no question that for all practical purposes the manner in which they should relate to the Minister is identical. The military profession has its own distinct traditions and values which are crucial in recruitment, in training and in the field, but it cannot claim a “higher loyalty” which distinguishes it from other servants of the Crown. Equally, while NZDF is not a government department and the Ministry is, the ethos which determines their relationship with the Government is the same and Ministers should have the same expectations of both in respect of service and support. It follows, therefore, that the same conventions which apply elsewhere in dealings between Ministers and their senior professional advisers should apply to the defence system also.

…

2.9 For my own part, while I fully agree that the constitutional principle of civilian control is an essential and permanent component of our defence system, I see it as being exercised by the Minister, Cabinet and Parliament and not by public servants. Both civilian and military defence officials enjoy equal status as servants of the Minister – one does not control the other, one should not predominate over the other. Their skills are complementary and should be fused in a partnership.

We agree.

- As we have said, decisions about where New Zealand troops are committed, and on what basis, are policy decisions for the Government. While the Minister of Defence is the Minister responsible for the formulation and implementation of the Government’s defence policy, the Cabinet has the power to override the Minister under the constitutional convention of collective ministerial responsibility. Obviously, decisions to send troops overseas and put them in harm’s way will closely involve the Prime Minister and Cabinet. But the important point for present purposes is that, constitutionally, there is no doubt that the decisions of successive governments to deploy troops to Afghanistan were decisions which they were entitled to make.

- While ministerial responsibility has numerous dimensions in the defence context, we need only make two points here about the Minister’s authority.

- First, the Minister must approve, or recommend to the Prime Minister for approval, the rules of engagement for missions abroad once satisfied they meet the proper legal requirements and are appropriate in policy terms. Rules of engagement are an important mechanism for the implementation of government policy during a particular deployment. Requiring that they be approved by the Executive maintains an element of democratic control and oversight over, for example, the circumstances in which NZDF personnel may use lethal force.

- Second, while there is no doubt about the power of the Minister to direct a deployment overseas, there is an issue about the Minister’s power in relation to operational matters. In his evidence at the Inquiry’s Public Hearing Module 1, Dr Mapp pointed out that different ministers took different approaches to their relationship with NZDF. He made the following observation:89

The Defence Act is couched in general terms to allow a degree of flexibility in how civilian oversight of the Defence Force is exercised. Oversight can be exercised in different ways depending on the needs of the specific deployment and the relationship between the Minister and the Chief of Defence Force.

- Dr Mapp said oversight occurred through regular briefings, both oral and written, from the Chief of Defence Force and other senior officers. The Minister emphasised, however, that he did not approve or select missions for the NZSAS within the Afghanistan context. On a day-to-day basis, the NZSAS operated under the ISAF umbrella. The operations were conducted according to approvals from ISAF but also in accordance with the New Zealand rules of engagement and within the Government’s caveats.

- The Policing Act 2008 makes it clear that the Commissioner of Police is not responsible to the Minister of Police, and must act independently, in respect of certain policing decisions of an operational nature.90 In contrast, the Defence Act contains no equivalent provision. This may reflect the fact that maintaining and utilising armed forces and defending the nation were originally within the royal prerogative and that the prerogative remains relevant. It may also reflect the fact that policing decisions are different in nature to military decisions.

- Legal advice provided to Mr Hunn’s 2002 review contains this statement from Professor Matthew Palmer, then at the Centre for Public Law at Victoria University:91

The extent of the powers conferred upon the Minister [by section 7 of the Defence Act] to direct the military is unclear at the margins, and untested in court. It is likely to be affected by the historical evolution of the prerogative in relation to defence matters and the scheme of the current defence legislation. We consider that, if tested in court, the Minister’s power would be likely to extend to control over general strategic decisions relating to the deployment of troops and politically sensitive decisions relating to foreign policy. It is unlikely to extend to specific operational decisions in a field of conflict which a court is more likely to find to be the preserve of the CDF. There is a legal grey area here and the circumstances which would test it would require an unfortunate conflict to develop between the Minister and CDF.

- While, in principle, it seems an attractive view that operational decisions in the context of a particular deployment should be the preserve of the Chief of Defence Force,92 we think the position much less straightforward than is the case with the police, for the following reasons:

- First, it may well be difficult to specify with precision in a military context what are and are not operational decisions. Put another way, the boundary between what is a policy decision and what is an operational decision may not always be self-evident.

- Second, in general, policing decisions relate to the application of the law to individuals subject to New Zealand’s jurisdiction. Separation of powers considerations require that ministers do not intervene in those decisions. By contrast, NZDF operations abroad do not generally affect individuals who fall directly within New Zealand’s jurisdiction.93 They are a means of defending New Zealand’s interests as a whole and giving effect to government policy and strategy on the world stage. Bias against, or unfair or inequitable treatment of, individuals through political interference is less likely in that context. Moreover (anticipating the next point), military operations are more likely to have significant political and policy implications and to require some form of government response than most operational policing decisions.

- Finally, although Dr Mapp said that he did not approve or select missions for the NZSAS in Afghanistan and that it was not his role to do so, he also said that there may be circumstances where the Minister should intervene to say that a particular operation should not be conducted, especially one in an overseas deployment where New Zealand’s international interests and obligations are engaged (or potentially engaged), as we now explain.

- As we noted at paragraph [65], under s 25(1)(b)(i) of the Defence Act the Chief of Defence Force is responsible to the Minister for carrying out NZDF’s functions and duties arising from the Government’s policies. As a member of the Executive, the Minister is accountable to Parliament for policies adopted and implemented. Even if operational decisions are, in general, outside the scope of ministerial authority, such decisions may nevertheless be of vital significance to the Government of the day.

- We take Operation Burnham as a convenient example. That was an operation which the Chief of Defence Force was required to approve if it was to go ahead because it was outside TF81’s usual area of operations. But it involved a high level of risk for the forces involved. It was possible that a helicopter carrying New Zealand troops could have been shot down, resulting in the deaths of New Zealanders and other coalition personnel. Such an event would undoubtedly have been a matter of great public and media interest in New Zealand and perhaps internationally. Within New Zealand, it may well have caused public controversy about, for example, New Zealand’s commitment of NZSAS personnel to ISAF operations in Afghanistan. This controversy might have led to scrutiny of one of the Government’s policy choices. Similarly, if coalition forces became involved in a major fire fight with known insurgents, during which New Zealand troops inadvertently killed civilians, the interests of the New Zealand Government would obviously be engaged given that issues of international accountability could arise.

- The Government has strategic goals for military deployments, and there is a range of potential legal and theoretically justifiable military actions within a deployment that might either help or hinder the achievement of those objectives. Hon Dr Jonathan Coleman, who succeeded Dr Mapp as Minister of Defence at the end of 2011, suggested in his evidence that the participation of New Zealand forces in particular operations may possibly at times be inconsistent with the Government’s overall strategic direction for the relevant deployment. In such a case it may be appropriate for the Government to intervene.

- The short point, then, is that some military decisions which might fairly be described as “operational” may potentially have significant governmental and political impacts, particularly those involving Special Forces engaged in operations overseas. This suggests that it is legitimate that the views of the Minister, and in some cases the Prime Minister, are sought before those decisions are implemented. We see this as an element of civilian control of the military rather than as an application of the “no surprises” policy.94

- This gives rise to a more general point about accountability to Parliament. Obviously, Parliament must pass any legislation addressing defence issues and a select committee is likely to consider proposed legislation as it moves through the House. But select committees have a broader role than simply perusing proposed legislation. They exercise financial oversight through hearings on estimates and through financial reviews; and beyond those obvious means of control, select committees can seek information on matters of special interest to them. For example, in relation to Afghanistan:

- In November 2010, the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Select Committee sought a briefing from NZDF on New Zealand’s rules of engagement in light of New Zealand’s obligations as a signatory to Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture, and that was provided.95

- In February 2011, the Committee received a briefing from the Minister of Defence on the NZPRT in Afghanistan and issued a brief report.96

- In August 2012, following the deaths of two NZDF personnel in Afghanistan, the Committee sought a briefing from NZDF on the situation there. The Chief of Defence Force indicated that he considered it was premature to provide a briefing in light of relevant announcements by the Government.97

- In addition to this, Mr Hunn, made an important observation in his 2002 review. He said:98

6.99 Over the past two decades the shift from the primacy of managing defence alliances (which is essentially an Executive function) to the emphasis on overseas deployments as partners in peacekeeping and peace support missions, has led to increasing Parliamentary interest in defence and its management. Recent Governments have chosen to involve Parliament in decisions to deploy the NZDF overseas on operations that may involve combatant situations. The decision to commit forces rests with the Government. However, because of the consequences for personnel deployed overseas and for the need to maintain public support, Governments have recognised that Parliament can play a valuable role in building a national consensus for such deployments.

The process leading to the deployment of New Zealand forces to Afghanistan in 2001 and later in 2009 illustrates Mr Hunn’s point.

- To summarise on this aspect, given that New Zealand law places the military under civilian control in the form of the Minister, and that the Minister is answerable in Parliament for the conduct of his portfolio, both NZDF and the Minister must ensure that there is effective accountability to the Minister by NZDF. Effective accountability requires the provision of accurate information. We consider that the Minister is entitled to expect full, accurate and timely reporting from NZDF as to the circumstances of events such as Operation Burnham. Ministers need to be in a position to provide well informed and accurate advice to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, to respond appropriately to questions in the House and from the media and, in some circumstances at least, to determine whether some form of government response is required. One of the matters that we will address in subsequent chapters is whether NZDF met its obligations to provide the Minister with full, accurate and timely information in connection with the allegations of civilian casualties during Operation Burnham.

- The foregoing discussion has focused on democratic accountability and control of NZDF through the Minister and Parliament. There are, of course, other mechanisms which facilitate democratic accountability and control, in particular:

- the mechanisms established under the Official Information Act 1981 for the release of official information;

- the obligation under the Protective Security Requirements to keep the classification of material under review so that once the need for classification has passed, the material can become publicly available; and

- the record-keeping requirements in the Public Records Act 2005, which are aimed at preserving the public record.

- The short point is that keeping proper records of official information and making them available for public scrutiny facilitates transparency and is an important precursor to proper democratic accountability. Transparency enables interested members of the media and the public to raise issues and may prompt Parliamentary interest. As will become apparent, this occurred in relation to detention issues in Afghanistan.99

- In his private evidence to the Inquiry, Dr Mapp said that he had already planned to travel to Afghanistan in August 2010 before the 3 August attack on the NZPRT patrol in which Lieutenant Tim O’Donnell was killed. He said that the trip took on a “new urgency” as a result of the attack. Dr Mapp was away from New Zealand in the period 17–24 August and was in Kabul with the Chief of Defence Force when Operation Burnham took place. He was given a briefing on the operation the day before it occurred. The briefing was not a full briefing of the type that those participating in the operation would have received but an abbreviated “overview”. After hearing the briefing, Dr Mapp considered that the Prime Minister should be informed of the operation because of its nature and in accordance with the “no surprises” approach.100 Dr Mapp said he understood that this was the biggest mission that New Zealand forces had carried out in Afghanistan and considered that it involved a significant element of risk, given that it was to take place in a remote and mountainous area which had to be accessed by helicopter and where there was an established insurgent presence. He considered that the possibility of significant New Zealand casualties could not be ruled out.

- A telephone call to the Prime Minister was arranged and after some initial discussion, the Minister asked the Chief of Defence Force to explain the operation to the Prime Minister, which he did. Dr Mapp said that the Prime Minister agreed to the operation proceeding. When the operation began, Dr Mapp was offered the opportunity to watch it with the Chief of Defence Force via a live video feed at Camp Warehouse.101 Dr Mapp said that while at a personal level he would have been interested in observing it given his military background, he decided that he should not take up the opportunity as it was an operational matter for the Chief of Defence Force rather than for him as Minister. Dr Mapp also told us that his report to Cabinet on his trip to Afghanistan did not refer to the operation for the same reason.

- As noted above, Dr Mapp said that he did not see his role as approving (or otherwise) individual operations in Afghanistan. Obviously, there was a national interest in Operation Burnham as it was intended to capture two insurgent leaders who had been involved in the 3 August attack. Even so, the decision to undertake the operation was a military one, approved first by the Chief of Defence Force and then by ISAF, which had agreed to provide considerable support in the form of air assets. From a military perspective, checks and balances were operating on the New Zealand side and the ISAF side. In addition, the operation was supported by Afghan authorities, who had issued arrest warrants for Maulawi Neimatullah and Abdullah Kalta.

- It is likely that, as Dr Mapp acknowledged, if the Minister or the Prime Minister had expressed some objection to, or concern about, the operation, the Chief of Defence Force would have taken that into account and decided not to proceed. In that sense, the opinion of the Minister or Prime Minister may have been influential or persuasive so far as the Chief of Defence Force was concerned. This was an operation which posed real risks to the soldiers involved and which may have had significant political repercussions if those risks had eventuated. But ultimately the decision to conduct the operation was a military one.

- In any event, it would have been surprising, in our view, if either the Prime Minister or the Minister had expressed an objection to Operation Burnham going ahead. We say this because:

- Despite the risks involved, there was a clear military justification for the operation. As described in more detail in chapter 3, the NZPRT commander had been concerned for some time at the increasing sophistication of attacks in Bamyan province where the NZPRT operated carried out by insurgents based in the neighbouring Baghlan province. These had culminated in the 3 August attack and the death of one of his men and injuries to others. Intelligence reporting indicated that the insurgents planned further attacks.102 Justifiably, the NZPRT commander considered that some form of response was required.

- As we have indicated above, one of the purposes of the deployment of the NZSAS in 2009 was to support NZDF elements in Afghanistan, essentially the NZPRT.103 So the operation was within the scope of the deployment as originally envisaged.

- As described in more detail in chapter 3, the approval process for the operation involved evaluations, first by NZDF and second by ISAF. Indeed, ISAF was prepared to commit considerable resources to it. Further, the Afghan Ministry of the Interior provided arrest warrants. Ministers were entitled to rely on the efficacy of these planning and approval processes.

- To summarise, the role of ministers involved approving the deployment and the rules of engagement, setting any national caveats and ensuring that appropriate arrangements with ISAF and with the Afghan Government were in place, so as to meet New Zealand’s international obligations. As a general rule, although they should be informed of operational decisions, ministers should not be involved in individually authorising or denying particular military operations and so taking ministerial responsibility for them. That said, we accept Dr Coleman’s point that there may be occasions where NZDF may need to check that particular operations fit within the Government’s strategic objectives for the deployment. Operation Burnham may have been such an occasion. In any event, Operation Burnham was an operation conducted outside the area of operations fixed by the Government for the deployment and so required the consent of the Chief of Defence Force under his delegation. It was not surprising then, that Dr Mapp wished to bring the operation to the Prime Minister’s attention.

- As noted, ministers must ensure that they are fully informed and are given full and regular briefings in relation to operations abroad, given the potential of such operations to cause public controversy and/or international concern. While the Government had the power to terminate the deployment of the NZSAS to Afghanistan, it did not have the power to directly control ISAF-approved operations (assuming the operation was within the Government’s mandate). Operational decisions rested in the final analysis with the Chief of Defence Force from a national command perspective and the Commander ISAF from an operational control perspective, although this was subject to the national “red card”.

Afghanistan: a little background

The New Zealand deployments to Afghanistan

The NZPRT in Bamyan

The NZSAS deployment in 2009

The nature of the NZSAS deployment as part of ISAF

Democratic accountability for, and control over, NZDF

Was Operation Burnham approved by ministers?

Figure 1:

Levels of military operations104

Figure 2:

Command and control organisational chart for NZSAS participation in Operation Wātea

1 Terms of Reference: Government Inquiry into Operation Burnham and related matters (11 April 2018), cl 7.4. This aspect of the Terms of Reference may reflect the fact that Hit & Run says that Operation Burnham was approved by the then Prime Minister, Rt Hon (now Sir) John Key, and that he “is uniquely responsible for what followed from his decision”: Nicky Hager and Jon Stephenson Hit & Run: The New Zealand SAS in Afghanistan and the meaning of honour (Potton & Burton, Nelson, 2017) at 120.

3 Thomas Barfield Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2012) at 1.

4 William Dalrymple The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Bloomsbury, 2019).

6 At 18.

7 Evidence of [name withheld] “Afghan Civilian Perspective” Transcript of Proceedings, Public Hearing Module 2 (22 May 2019) at 17; and UNESCO Institute for Statistics “Afghanistan: Education and Literacy” <uis.unesco.org>.

9 At 15.

11 Cornelius Friesendorf How Western Soldiers Fight: Organizational Routines in Multinational Missions (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018) at 172.

12 Christina Lamb Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan to a More Dangerous World (William Collins, London, 2015) at 310.

13 The same is unlikely to be true of weapons such as rocket-propelled grenade launchers and machine guns, however, which are likely to be associated with insurgent or militia activities.

14 Crown Agencies “New Zealand Government’s decisions to deploy New Zealand forces into Afghanistan” (Public Hearing Module 1, 4 April 2019) at 1.

16 We will not set out a full list of the Security Council resolutions relating to Afghanistan over the period of New Zealand’s involvement. A complete list can be found in annex B to Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade “An overview of Afghanistan, its history, New Zealand’s relationship with the country, the international response to 9/11, current security situation” (Public Hearing Module 1, 4 April 2019).

18 The Agreement was signed at Bonn on 5 December 2001 at a meeting convened by the United Nations.

19 The Transitional Authority was appointed in June 2002, after some delays, by a Loya Jirga (“grand assembly”). It governed the country until presidential elections could be held in 2004. Hamid Karzai, the chairman of the Interim Authority, was also appointed as the president of the Transitional Authority in 2002 and was subsequently elected as president in 2004.

20 “NATO takes on Afghanistan mission” (11 August 2003) NATO <www.nato.int>.

21 The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) was formed to better support the implementation of the Bonn Agreement by integrating all the existing United Nations elements in Afghanistan into a single mission. Its mandate included fulfilling tasks and responsibilities relating to human rights, the rule of law and gender issues; promoting national reconciliation and rapprochement; and managing all United Nations humanitarian relief, recovery and reconstruction activities in Afghanistan (The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security UN Doc A/56/875–S/2002/278 (18 March 2002), endorsed in SC Res 1401 (2002)).

22 United States Army Combined Arms Center Afghanistan Provincial Reconstruction Team Handbook: Observations, Insights and Lessons (February 2011) Center for Army Lessons Learned at 3.

23 Rt Hon Sir Kenneth Keith “The international legal framework” (Public Hearing Module 3, 29 July 2019) at 5. Crown Agencies agreed this was the position (see Paul Rishworth QC “The International legal framework” (Public Hearing Module 3, 29 July 2019) at [11]), and the non-Crown core participants did not dispute it.

25 A timeline of New Zealand’s involvement in Afghanistan is included in “New Zealand Government’s decisions to deploy forces to Afghanistan”: Crown Agencies, above n 14, at annex one.

26 (3 October 2001) 595 NZPD 524.

27 Operation Enduring Freedom was launched by the United States on 7 October 2001, with United Kingdom support.

28 (3 October 2001) 595 NZPD 548.

29 Military Technical Arrangements between the Government of New Zealand and the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (12 August 2009), a copy of which is contained in: Arrangement Between Afghanistan MFA and NZDF concerning the Transfer of Persons between the NZDF and Afghan Authorities (12 August 2009) (Inquiry doc 05/32) from 5 onward. See also NZDF brief – 13 Apr 2010 (14 April 2010) (Inquiry doc 13/23) at 2.

30 See CDF OP DIRECTIVE 21-2009 (July 2009) (Inquiry doc 12/11) at [22], noting that Task Force 81 (TF81) would be covered by the Military Technical Arrangement between New Zealand and Afghanistan when conducting national tasks.

31 “ISAF’s mission in Afghanistan (2001–2014)” (1 September 2015) NATO <www.nato.int>.

32 Ron Crosby NZSAS: The First Fifty Years (Penguin Group, Auckland, 2009) at 345–346.

33 Thomas Barfield The War for Afghanistan: A Very Brief History (Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 2012) at 6; see also Antonio Giustozzi “The Taliban Beyond the Pashtuns” The Centre for International Governance Innovation (5 July 2010) at 4.

35 See Oxfam The Cost of War; Afghan Experience of Conflict, 1978–2009 (November 2009) at 11–12, 14; Danish Immigration Service Danish Immigration Service: Report on fact-finding mission to Pakistan to consider the security and human rights situation in Afghanistan (18 to 29 January 2001) (November, 2001) at [1.1]; Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch World Report 2000—Afghanistan (December 1999).

37 Sir Angus Houston “The military context” (Public Hearing Module 1, 4 April 2019) at 4; Evidence of Sir Angus Houston, Transcript of Proceedings, Public Hearing Module 1 (4 April 2019) at 20–21. COIN is an abbreviation for Counter-Insurgency.

38 Hon Mark Burton, Minister of Defence “New Zealand to lead Provincial Reconstruction Team in Afghanistan” (8 July 2003) <www.beehive.govt.nz >.

39 Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade “New Zealand’s Achievements from 10 Years of Development Assistance in Bamyan, Afghanistan” (Public Hearing Module 1, 4 April 2019).

40 NZDF “Chief of Defence Force: Bamyan Mission Accomplished” (5 April 2013) <www.nzdf.mil.nz>.

41 Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade “New Zealand’s achievements from 10 years of development assistance in Bamyan, Afghanistan”, above n 39, at 4.

42 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade advised that since 2001 New Zealand has invested approximately NZ$100m in development initiatives in Afghanistan at the national, regional and provincial level: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade “An overview of Afghanistan…”, above n 16, at 2.

43 SC Res 1776 (2007) at 1.

46 Some relevant Cabinet papers have been disclosed publicly by the Inquiry: 16 February 2009 Cabinet Decision Minute – Afghanistan: NZ’s contributions beyond Sept 2009 (16 February 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/02); 3 July 2009 Cabinet Paper Cover Sheet – Afghanistan: 2009 Deployment of the NZSAS (Operation Watea) (3 July 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/03); 6 July 2009 Cabinet Decision Minute – Additional Item Afghanistan: Power to Act for Group of Ministers (6 July 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/04); 7 August 2009 Cabinet Paper – Review of NZ’s Commitment to Afghanistan (7 August 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/05); 10 August 2009 Cabinet Decision Minute – Afghanistan 2009: Deployment of NZSAS (10 August 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/06); and 10 August 2009 Cabinet Decision Minute – Review of NZ’s Commitments to Afghanistan (10 August 2009) (Inquiry doc 01/07). See also Evidence of Hon Dr Wayne Mapp, Transcript of Proceedings, Public Hearing Module 1 (4 April 2019) at 72–78.

48 The CRU was a police unit in the nature of a SWAT or tactical operations team.

52 At the time National led a minority government with confidence-and-supply agreements with the Māori Party, as well as ACT and United Future.

53 (18 August 2009) 656 NZPD 5605.

54 (18 August 2009) 656 NZPD 5603.

55 (18 August 2009) 656 NZPD 5609.

57 Antonio Giustozzi The Taliban at War 2001—2018 (C Hurst & Co (Publishers) Ltd, London, 2019) at 1.

59 At 45.

60 Discussed further in chapter 3.

61 For a description of the COIN strategy, see United States Government “Counterinsurgency Guide” (January 2009) Bureau of Political-Military Affairs <www.state.gov> and General Stanley McChrystal “ISAF Commander’s Counterinsurgency Guidance” (27 August 2009) NATO <www.nato.int>.

62 See, for example, Human Rights Watch ‘Troops in Contact’ Airstrikes and Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan (September 2008); United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission Afghanistan—Annual Report 2010: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict (March 2011).

63 See, for example, Amnesty International Left in the Dark—Failures of accountability for civilian casualties by International Military Operations in Afghanistan (August 2014).

65 For a helpful discussion of the development of ISAF’s approach, see Sahr Muhammedally “Minimizing civilian harm in populated areas: Lessons from examining ISAF and AMISOM policies” (2016) 98 Int Rev of the Red Cross 225, at 232–238.

66 This was later renamed the CIVCAS Data Tracker database. See, for example, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Compilation of Military Policy and Practice: Reducing the humanitarian impact of the use of explosive weapons in populated areas (August 2017) at 49.

67 Jim Garamone “Directive Aimed at Minimizing Civilian Casualties” American Forces Press Service (16 September 2008) US Department of Defense <archive.defense.gov>.

68 Headquarters ISAF “Tactical Directive” (6 July 2009) NATO <www.nato.int>.

69 Other Tactical Directives were issued dealing with matters that affected the civilian population such as driving (emphasising that troops should drive safely rather than aggressively) and night raids (limiting their use unless other options were not feasible).

70 General David Petraeus Confirmation Hearing (29 June 2010) C-Span <www.c-span.org>.

71 ISAF Public Affairs Office “Gen. Petraeus updates guidance on use of force” (4 August 2010) U.S. Central Command <www.centcom.mil>. Discussed further in chapter 3.

72 Joseph Felter and Jacob Shapiro “Limiting Civilian Casualties as Part of a Winning Strategy: The Case of Courageous Restraint” (2017) 146 Daedalus 44.

74 See, for example, NZDF “New Zealand Defence Doctrine” (November 2017) <www.nzdf.mil.nz>.

75 At 12.

76 This brief description is drawn from chapter 3 of NZDF Foundations of New Zealand Military Doctrine (2nd ed, November 2008) <www.nzdf.mil.nz>, which was current at the time of the events under review.

77 For a full discussion, see NZDF “New Zealand Defence Force Command and Control” (May 2016).